The Ghosts of Ecton and the Haunting of William Hogarth

A curious instance of a time slip and simultaneous haunting allegedly occurred in a neighbouring village close to where I grew up. This story so excited my young mind as a boy that, when I first read the Legend of Lucy Lightfoot in The Unexplained magazine as a boy in the late 1970s, it became the “validation” of a certain local myth that I had longed for. Obviously, I did not know then that Lucy Lightfoot was a work of fiction.

When I was a child a story was relayed to me about ghostly happenings and strange time slip phenomena during the artist William Hogarth's stay in the village of Ecton in Northamptonshire in the late 1740s. The person who told me this story was well over ninety years of age at the time. The provenance of her account no doubt went to the grave with her more than half a century ago, but I understand that a contemporary eighteenth-century account exists in The Covent Garden Journal written by Henry Fielding (1707-1754). Fielding was a friend of the well-known caricaturist and satirist William Hogarth (1697-1764). They lived close to one another in London, for many years.

Both men shared a common sense of humour and appeared to have encouraged one another to “go one step further” in their satire of society's shortcomings each time they met. For Fielding, this ultimately led to his famous 1749 novel 'The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling'. Fielding would also write biographical pieces for The Covent Garden Journal, and many such stories featured the colourful life of William Hogarth. This is recounted below, but it needs to be remembered that Fielding might have been pulling his readers' legs.

One interesting aside, before we begin, concerns Hogarth's picture entitled Time Smoking a Picture painted in 1761 (below), which is superficially a satirical comment on critical snobbery of art. However, on another level, it can clearly be seen that personified “Time” breathes smoke into the portrait, and so there is a serious allegorical message to the picture.

First, a little background on William Hogarth. He was the eldest surviving child of nine. Much of his childhood was spent living through the traumatic events of his father's bankruptcy in a day and age with no welfare state and when unpaid debt was a criminal offence. Richard Hogarth, William's father, had opened a coffee house in London but the venture failed, and he was forced to move his entire family into lodgings within “the Liberties of the Fleet.”

The Liberties were controlled by the Fleet Prison, which stood beside the (now lost) River Fleet in London. Here Richard Hogarth had to work to pay off his debts. The site today is a pleasant green square surrounded by housing and artisan galleries. At that time the gaol accommodated several hundreds of prisoners and their families.

This was very different from a modern prison, and strict class divisions prevailed, such that the Fleet had what was termed the “Common Side” where prisoners were incarcerated in cells, and “the Master's Side” where rent was paid to live within the Liberties, financed by working prisoners. Little more than a decade after his father's release, the warden of the Fleet was imprisoned for acts of cruelty towards the prisoners and for their financial exploitation.

For the Hogarths, the experience must have been frightening, and no doubt it left an indelible impression upon the young William, who remained in the Liberties until he was about fifteen. Indeed, Hogarth is said to have experienced his first paranormal encounter shortly after the family relocated to the Fleet, when he awoke to the horrifying vision of a demon standing close to his bedside. When he was nineteen Hogarth experienced another supernatural phenomenon. He had just gone to bed and was still wide awake when he saw a disembodied head at the foot of his bed. It was life-size, and luminescent orange in colour, and yet no discernible source of energy was external to it. A few days later, a Bible on his bookcase fell next to him and, not long after, Hogarth heard a deep disembodied voice within his room.

In 1713, Hogarth was apprenticed to an engraver, and by the early 1720s was self-employed as a printmaker. Around 1724 he became one of the original subscribers to the “Academy for the Improvement of Painters and Sculptors by Drawing from the Naked" in St Martin's Lane, London. In 1729, he eloped with Jane Thornhill, the daughter of the respected Sir James Thornhill, an artist who ran a rival academy. The two men would eventually settle their differences, and in March 1733 Sir James even accompanied his son-in-law to sketch the notorious multiple-murderer Sarah Malcolm in the Fleet Prison, a few days before she was hanged on the Tyburn Tree.

After his father-in-law's death in 1734, Hogarth established his own academy, and in 1757, he was appointed Serjeant Painter to King George III and died in London on 25 October 1764.

The Ecton Visit

In the Summer of 1749, Hogarth found himself in the small Northamptonshire village of Ecton. The request to go there was made by his friend and fellow Great Queen Street Freemason, the Reverend John Palmer, the local Rector. Like Hogarth, Palmer was a philanthropist and concerned with the plight of the poor, particularly the education of children.

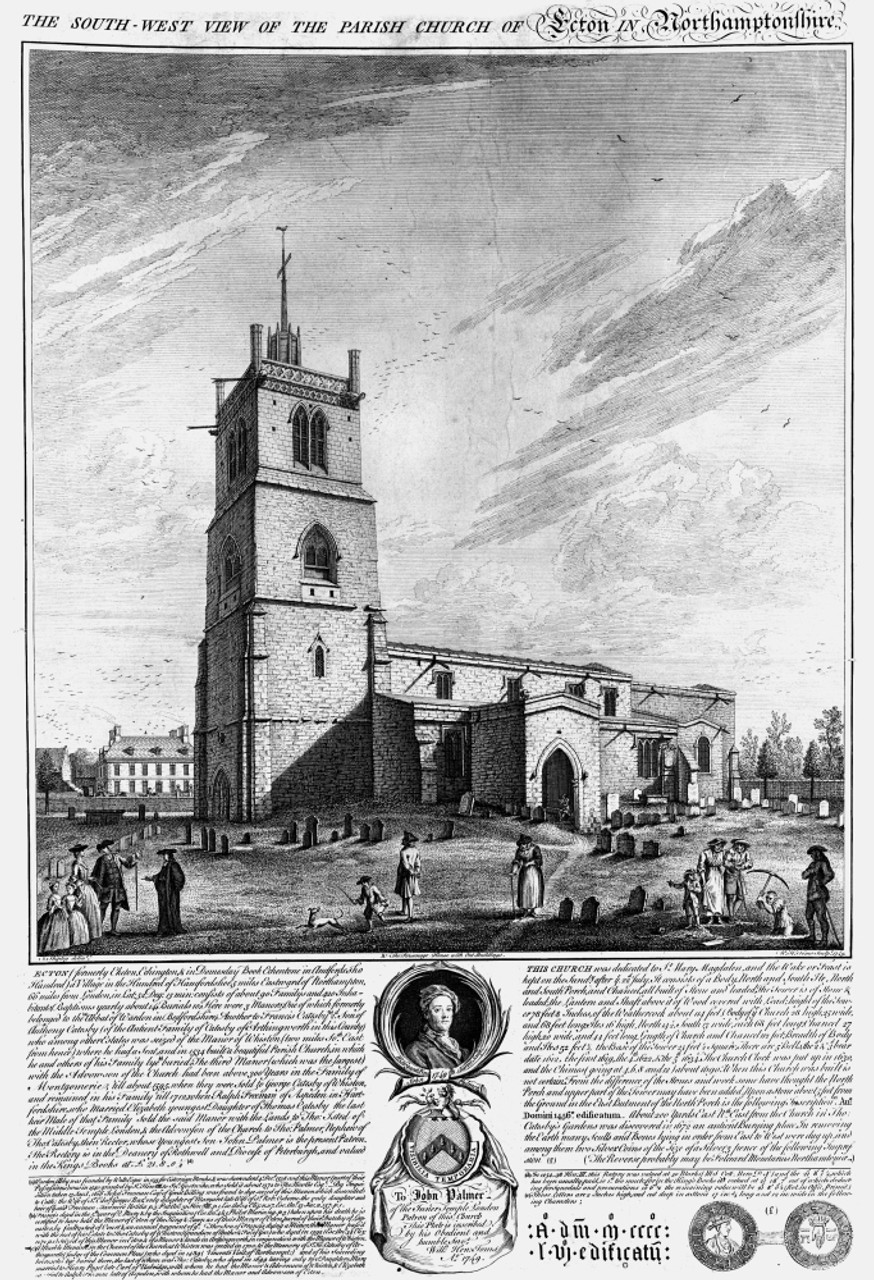

With the assistance of a suitable property donated by Anne Isted, the wife of Ambrose Isted, the Lord of the Manor at Ecton, Palmer established a free school for the poor and shortly thereafter commissioned Hogarth to engrave his portrait and a picture of the parish church. Hogarth's good friend, Benjamin Franklin, then resident in England, had also expressed a desire to visit the village with him but was awaiting the arrival of his son William from the American colonies, whom he desired to accompany on account of his father having been born in the smithy at Ecton. Thus it was that in July 1749 Hogarth travelled north alone.

William Hogarth

The coach from London took several days, stopping overnight at St Albans and Bedford. He may have spent the night prior to his arrival in Ecton at the Black Lion Inn in Northampton's Marefair, or in one of the coaching inns along Bridge Street situated just within the ruins of the old town wall. Curiously enough, the stables at the Black Lion were used as holding cells for prisoners being tried at the assizes held at the remaining buildings within the castle grounds. William might well have noticed that the townspeople were still upset by Cromwell's refusal to pay for the shoes they had provided for his New Model Army, a dishonoured contract that did not spare the town's fortifications from an avenging King Charles II at his Restoration in 1660. Hogarth may also have been told about the oft-sighted restless spirit of a Royalist thrown down a well in the yard of a nearby smithy.

Upon approaching Ecton from the direction of Northampton, Hogarth may have observed that the road dipped down in front of an ancient inn then known as The Globe. Built in the previous century, it was renamed the World's End in 1765 when it was reconstructed. It is haunted, say some, because of the terrible treatment meted out to Royalist soldiers imprisoned on the site following the Battle of Naseby in 1645. Others have said it was used as a hospital. Whatever the reason, The Globe was considered a haunted place in Hogarth's time.

The existence of ghosts is a divisive subject, I readily admit. Yet, it was while staying at the Rectory with the Reverend Palmer and his family that William Hogarth is said to have experienced the first of many inexplicable ghostly occurrences. Or so the story goes. Believe what you will, but there is no reason to doubt our own senses, let alone the vast history of reported occurrences down the long centuries of man's existence. Once Hogarth discounted other causes (such as rats or Palmer's servants moving around the building), he found the occurrences so regular and disconcerting that he began to keep a diary of them.

My own research has not revealed evidence of Hogarth's journal, thus what follows may be the conjecture of an elderly villager who has long since passed.

The Ghosts of Ecton Rectory

After a few peaceful nights at the Rectory, at two o'clock in the morning, Hogarth was awoken by a single light tap coming from ‘within' the chest of drawers next to his bed. Similar sounds occurred between three and four o'clock in the morning. There followed a knocking sound from the ceiling.

On a couple of occasions in the early hours, there was a crashing sound in the house, like a heavy object such as a wooden chest being dropped. This phantom sound often came from the direction of Palmer's children's rooms, but they were always fast asleep. No one else heard or was awoken by it, and nothing was moved in the house that Hogarth could discern. He naturally suspected a prank; and, when it happened again in July, he leapt from his bed only to find no one there, and even Palmer's dog lay undisturbed in her sleep, and who normally barked at everything. A case perhaps, of what Ben Franklin once described to him as “exploding head syndrome”, except that Palmer's wife heard a similar crashing sound on another occasion in the house, but not during the night. These crashes, thuds and explosive sounds continued for the duration of his stay on the property.

In mid-August, at about eleven o'clock at night, Hogarth was working on Palmer's portrait when there came a thud from the ceiling above his room. There was nothing there save the loft space between the room and roof tiles. The following day, Mrs Palmer discovered a shelf broken in her pantry; also, the front door lock was no longer working, and none of the keys would fit. At midnight, there was a single loud tap from Palmer's daughter's room and a creak on the landing at one o'clock in the morning. At two o'clock, there was a loud single bang. The bang sounded like a large object landing.

Hogarth raised these matters with Palmer who, being a man of many interests in matters of the hidden invisible world, took matters seriously. He had said that the family had experienced these occurrences for many years and that his late father (also a clergyman) had noticed them. The family had become accustomed to them, but matters had taken a turn for the worse with the death of Thomas Isted many years earlier, in 1731. The Isteds occupied the neighbouring manor of Ecton House (now known as Ecton Hall) and the parish church and Rectory lay close to its west wing.

On his death, his fourteen-year-old son, Ambrose Isted, inherited the estate but had always taken a great dislike to the proximity of the villagers of Little Ecton to the south of his home, whose houses obscured the view of the valley, and of the proximity of the village buildings to the north which he regarded as being too close.

Ambrose had expended not inconsiderable effort planting trees and buying up properties to secure his privacy. He was unpopular in the village for being an avid supporter of the legislation permitting landowners to “enclose” their land and evict smallholder tenants. Indeed, at the time of Hogarth's visit to Ecton, there was much talk in the village about the redirection of the roads and the enclosure of common land. This was about to change the old agrarian society forever.

Palmer pointed out to Hogarth that before the Reformation the site of the Rectory had been a convent, and several graves had been uncovered of the nuns buried there. The grounds of the convent had spread over into the grounds now occupied by Ecton House, which at the time of the Dissolution benefitted from the sale of Church land.

What follows is pertinent to our story. Ambrose Isted had successfully petitioned for permission to close a road which ran in front of Ecton House. This road connected Ecton with the houses in Little Ecton, which at the time surrounded the manor. This prevented the villagers from moving about easily but gave Ambrose Isted a private driveway in front of his house. He had also protected his gardens by digging a “ha-ha” ditch at the southern extent of his grounds to prevent cattle (and villagers) from encroaching out of the remaining common land and ramshackle houses in Little Ecton. The Isteds pretentiously renamed their manor house Ecton Hall, to better reflect its grandeur. It was during this period that the graves of persons who were believed to have been nuns from the old priory at the site were disturbed by Ambrose's builders. Clearly, these activities by relative newcomers to the village disturbed whatever elemental forces lay resting in the area, not least on the grounds of the neighbouring Rectory itself.

Following Hogarth's conversations with Palmer, he became more attentive to the various ‘goings at the Rectory. One morning he arose early before the servants had unlocked the door, to discover his riding boots placed on a tall table. There was also a curious, thick atmosphere about the place. Stepping out into the courtyard Hogarth saw the figure of a tiny woman, no higher than four and a half feet tall, move from the direction of the stables and through an adjoining wall. Her form appeared completely solid – as solid as any living person. Indeed, William would have considered her an intruder or an eccentric villager, but for the figure's sudden disappearance as she strode through solid stone. He reported this to the Palmers who had not experienced anything like this themselves, but who described having had shoes and other items inexplicably placed on tables and shelves overnight by some mysterious force. Events, however, were to take a turn for the worse.

Later that day, John Palmer reported that while he was working on his sermon a book fell from the latch case. In fact, several other books, including an old family Bible, appeared to have been moved. Their daughter cried from upstairs, and it transpired her bedroom door had slammed closed on its own accord. At six o'clock that same evening, having returned from a day in Northampton to reprovision his inks and paper for the portrait he was working on, there came two distinct knocks on the floor of Hogarth's room, but the Palmers and their children were visiting the Isteds and none of the servants were upstairs. It was then that he heard the villagers living close by the Rectory bashing their pots and pans very loudly inside their homes. The following day he stopped one of them to ask what on earth they had been doing and why. The response he received was that the Isteds had disturbed Christian burials in their works at the house and that ghosts were manifesting about the village. The villager relayed to Hogarth how he had heard distinct knocking on his kitchen door when no one was there. When the rest of the family were asleep, his wife had been awoken by a loud knock at half-past one in the morning, and there then followed a series of raps from their room, together with the sounds of movement. It was local custom to frighten off ghosts by making loud noises (and, the villager added, it annoyed Ambrose Isted).

Returning to the Rectory, Hogarth found the house deathly quiet with a thick atmosphere of utter stillness, and only the clock in the hallway downstairs could be heard. When he was about to drift into sleep, these same sounds were repeated. At two o'clock A.M., there was a distinct, single noise in his bedroom, and half an hour later there was a tapping noise from the drawers. At a quarter to seven in the morning, just as the light was entering his room, there was a knocking sound from somewhere within the wall space close to him. Upon investigation, these sounds appeared to be coming from within the oak panelling itself, like an energy contained in the wood.

In late August Hogarth was nearing completion of John Palmer's portrait and began work on the image of the parish church his patron wanted when he heard a loud bang coming from the loft. Mrs Palmer was with him but heard nothing. Worryingly, at eight o'clock in the morning William distinctly heard his wife Jane's voice calling out to him in the Rectory - but who was fifty-five miles distant in London. He then experienced a strange dream, of the type Ben Franklin would describe as a “somnambulist attack”. In it, a spirit drew his wife's body from her bed so that she was levitating. Hogarth tackled the spirit to bring her back down but there was a lake filled with shadow people. The dream culminated when a woman rescued his wife and expelled the spirit. His dream did not have a definite ending, since he was awoken by movements within his room. The form and shape of the nun he had seen in the courtyard had materialised close to him, and she seemed to be looking directly at him and saying something, but no words left her mouth. Her face was lifeless and pale, and her eyes were jet black. As suddenly as she appeared, so she was gone.

That was enough for Hogarth, who immediately left the Rectory to take up lodgings at the inn. He gave his apologies to the Palmers, who had experienced a bad day themselves when their carriage wheel broke while driving them home from a church meeting in Northampton. Their horse also became sick and died that same day. Mrs Palmer also began reporting bad dreams in which she was being attacked by a relation. It was while staying at the inn that the strangest part of this story occurs, and that which relates most closely to the legend of Lucy Lightfoot. During a particularly brutal Summer thunderstorm in an early evening in September, with lightning crashing about, and heavy rain hammering down on the inn's narrow windows, Ambrose Isted and his family suddenly burst in through the inn's door (then at the south of the building, where the road once ran), almost collapsing over themselves, their clothes completely drenched and as white as sheets.

Trembling with terror their driver dashed in behind them and slammed the door shut, with his back to it, hand on the handle, frozen in blind terror. The innkeeper, Hogarth, and the handful of locals drinking in there were stupefied when Isted was sufficiently recovered with a glass of brandy wine and recounted to them what had just taken place.

Isted was being driven home with his wife and children and their coach was nearing Ecton when the storm broke. The driver carried on, but the horses were increasingly nervous with each thunderclap. When the lightning began, the driver was forced to pull over, put on the brakes, and calm the team as best he could. The village should have been in sight, and indeed, as it was normally still light at that time of year, would have been in full view. The storm, however, had darkened the sky, and the road from Northampton to Wellingborough was lined with elm trees which added to the overall gloominess of the atmosphere. It was then that the driver saw a small, dark figure standing in the middle of the road ahead. He called out, but the figure did not respond. He also noticed something else that was odd, namely that the lights from the village were of a different quality, and the outline of the structures was very different and looked much older. He called out to Ambrose, who was irritated at being asked to leave the comfort of the carriage to enter the deluge, but at the insistence of the driver who held the startled horses, he had no real choice in the matter. Approaching the figure, Isted also noticed that the road itself seemed different from usual, with displaced and more numerous trees. The crossroads ahead also appeared narrower, and more like the meeting of quiet country lanes. The lights from the village did not appear as they should, and he could swear the church tower was shorter.

As he approached, the figure in the torrential rain appeared to be that of a woman dressed entirely in black. She had her back turned to him, and was about four and a half feet tall. Isted called out asking if she required assistance. The woman ignored him and, keeping a wary distance, Isted moved around and saw that she was a nun. This was not right, since in England at that time the Catholic religion had long been prohibited, and the old faith was suppressed. She was about thirty, perhaps a little older, pale and wore a nun's habit. Upon closer inspection, Ambrose noticed that the habit was in fact dark grey, and tied around her waist was a cloth belt. Her sullen face was framed in a white wimple and veil, attached to a woollen cloth worn over her shoulders. She did not speak and, as suddenly as Isted blinked, her face became a decaying skull. Dead, arcane eye sockets instead of living organs met his horrified gaze. He froze in terror, and recovering his senses fell backwards, crashing into the mud, then ran back to the carriage screaming at the driver to “make haste and drive it down!”. His driver was caught off-guard and climbed up to release the brake. As he passed by the figure, he too saw the face was a skull. Terrified by the spectre, he lashed at the horses and the carriage raced past the horrible visage. As he approached the inn, the driver noticed that the building was much smaller and more dimly lit than usual, and a bend in the road was different. The carriage skidded to a halt, and the entire complement raced to the door of the inn only to find it bolted. Indeed, the door was different and unfamiliar to them, much older, and they hammered on it as the dreadful apparition of the nun moved towards them, its chop-fallen skull grimacing with the air of death. It was then that the door appeared to transform back into what it should have looked like, and they burst through into the building.

I am not aware of any further sightings of this ghostly nun, although there have been reports of paranormal occurrences in or around the World's End over the years. While the entire legend may have been the concoction of the imaginings of a lonely old Victorian who enjoyed entertaining children with stories, the appearance of the nun was indeed a reported apparition. As for the World's End, there have been sightings of shadowy, partially submerged figures walking in the cellar at the original ground level. I have also heard tell of a sighting in the nineteenth century of a headless man walking a lane between Ecton and a nearby village. Whether this event occurred or not is unknowable, and it may relate to the birth (sometime in the seventeenth century) of a headless baby close by in Mears Ashby, and the subsequent witch trials undertaken there by the infamous Witchfinder General, Matthew Hopkins. Indeed, the last trial of a witch in England took place at Mears Ashby in 1785. A local woman, Sarah Bradshaw, was accused by neighbours of being a witch and sunk in the village pond. She survived the ordeal, but it tells us much about the superstitions of local people in the area at that time.

Following the events of that fateful night, Ambrose Isted became a changed man. Although he continued to buy and enclose land, he was renowned for his kindness and generosity to the poor and dispossessed, and for greatly improving the living conditions of the villagers. He re-homed those moved into improved properties. Indeed, Ambrose gladly acquiesced to his wife's request for funds to pay for John Palmer's school for the poor children, and the Isted family grew in wisdom and charity for the remainder of their tenure at Ecton Hall.

As for Hogarth, he ran out of money while staying in the village and was unable to pay the landlord for his lodgings. Determined not to return to the Rectory, he agreed to paint the innkeeper a picture called The World's End. After Hogarth finished his commission for Palmer and left the village in early October, the innkeeper proudly displayed the painting outside the inn for many years. Eventually, like the ghostly nun and all memories of the local witch trials, it vanished from history and all records. Hogarth's friend Benjamin Franklin and neighbour Samuel Johnson visited Ecton in 1758 and 1764 respectively, no doubt inspired by his tales of time slips and ghostly apparitions.

Excerpt taken from the book 'Time Slip Phenomena: The Ghosts of the Trianon, The Legend of Lucy Lightfoot and the Haunting of William Hogarth' and (c) M.R. Osborne 2024