The Good Thief and that "other guy"

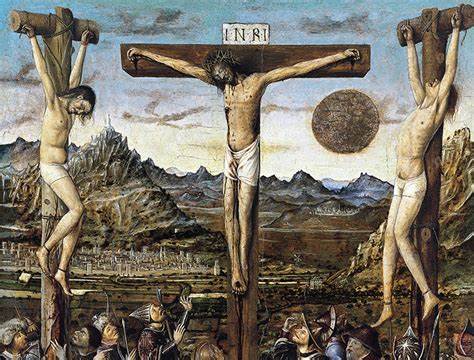

Did you know the word “steal” appears at least 35 times in the Bible? I was contemplating this little factoid last week when the story of the Good Thief and the "other guy” crucified alongside Christ sprang to mind.  You may recall, these were the Good and the Bad Thieves who died alongside him. The impenitent thief mocked Christ – despite his own position – and never acknowledged his guilt by apologising. The bad thief only wanted his cross taken down and removed from sight, so that he could carry on as before without any repercussions.

You may recall, these were the Good and the Bad Thieves who died alongside him. The impenitent thief mocked Christ – despite his own position – and never acknowledged his guilt by apologising. The bad thief only wanted his cross taken down and removed from sight, so that he could carry on as before without any repercussions.

Dismas the penitent thief, on the other hand, rebuked the bad thief by stating:

"Have you no fear of God, for you are subject to the same condemnation? We have been condemned justly, for the sentence we received corresponds to our crimes, but this man [Jesus] has done nothing wrong" (Luke 23:40-41).

The story is not about Christ. It is about our conscience, and the need to stand up, own and admit when we are wrong and accept accountability. Above all else, it is the power of apology to transform ourselves and our relationships. It is about that duality within us to be selfish or sharing - and which of these we deign to choose each day. It is about choosing between the true and the false in our daily conduct at work, in business, livelihoods and friendships.

to choose each day. It is about choosing between the true and the false in our daily conduct at work, in business, livelihoods and friendships.

The story of Dismas and the other guy is not even about theft (which can occur inadvertently anyway – such as the finders' keepers ‘rule' where we do not bother to look for the owner). No. Dismus admitted he was wrong and that it wasn't just ‘undue diligence' in getting found out. No. Dismus opened his heart to the transformative power of contrition.

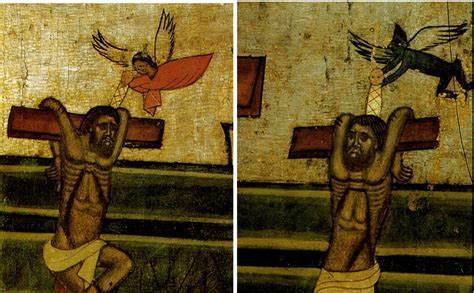

By the way, the other guy had a name too: Gestas. Although he was impenitent and only wanted “to get away with it”, he was unable to because he got caught. Indeed, he was publicly crucified. If he had had any common sense, then Gestas might have tried Pascal's Wager as a safe bet at that point - not that it would have moved his conscience. Only the power of apology could do that.

Knowing the name of the impenitent thief makes it so much more personal. Yet it points to only one obvious conclusion: it is always personal.